Nassau Agreement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Nassau Agreement, concluded on 21 December 1962, was an agreement negotiated between

Britain's nuclear weapons armament was initially based on

Britain's nuclear weapons armament was initially based on

Confronted with the same problem, the

Confronted with the same problem, the  A crucial reason for Skybolt's survival was the support it garnered from Britain. Blue Streak was cancelled on 24 February 1960, subject to an adequate replacement being procured from the US. An initial solution appeared to be Skybolt, which combined the range of Blue Streak with the mobile basing of the Blue Steel, and was small enough that two could be carried on the Vulcan bomber. Armed with a British

A crucial reason for Skybolt's survival was the support it garnered from Britain. Blue Streak was cancelled on 24 February 1960, subject to an adequate replacement being procured from the US. An initial solution appeared to be Skybolt, which combined the range of Blue Streak with the mobile basing of the Blue Steel, and was small enough that two could be carried on the Vulcan bomber. Armed with a British

The Kennedy Administration adopted a policy of opposition to independent British nuclear forces in April 1961. In a speech at

The Kennedy Administration adopted a policy of opposition to independent British nuclear forces in April 1961. In a speech at

These discussions were reported to the House of Commons by Thorneycroft, leading to a storm of protest. Air Commodore Sir

These discussions were reported to the House of Commons by Thorneycroft, leading to a storm of protest. Air Commodore Sir

In the wake of the Nassau Agreement, the two governments negotiated the

In the wake of the Nassau Agreement, the two governments negotiated the

President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

, John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, and Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as "Supermac", he ...

, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern pr ...

, to end the Skybolt Crisis. A series of meetings between the two leaders over three days in the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

followed Kennedy's announcement of his intention to cancel the Skybolt

The Douglas GAM-87 Skybolt (AGM-48 under the 1962 Tri-service system) was an air-launched ballistic missile (ALBM) developed by the United States during the late 1950s. The basic concept was to allow US strategic bombers to launch their weapon ...

air-launched ballistic missile

An air-launched ballistic missile or ALBM is a ballistic missile launched from an aircraft. An ALBM allows the launch aircraft to stand off at long distances from its target, keeping it well outside the range of defensive weapons like anti-aircra ...

project. The US agreed to supply the UK with Polaris submarine-launched ballistic missiles for the UK Polaris programme

The United Kingdom's Polaris programme, officially named the British Naval Ballistic Missile System, provided its first submarine-based nuclear weapons system. Polaris was in service from 1968 to 1996.

Polaris itself was an operational system ...

.

Under an earlier agreement, the US had agreed to supply Skybolt missiles in return for allowing the establishment of a ballistic missile submarine base in the Holy Loch

The Holy Loch ( gd, An Loch Sianta/Seunta) is a sea loch, a part of the Cowal peninsula coast of the Firth of Clyde, in Argyll and Bute, Scotland.

The "Holy Loch" name is believed to date from the 6th century, when Saint Munn landed there afte ...

near Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

. The British Government had then cancelled the development of its medium-range ballistic missile

A medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) is a type of ballistic missile with medium range, this last classification depending on the standards of certain organizations. Within the U.S. Department of Defense, a medium-range missile is defined by ...

, known as Blue Streak

Blue Streak or Bluestreak may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Blue Streak'' (album), a 1995 album by American blues guitarist Luther Allison

* Blue Streak (comics), a secret identity used by three separate Marvel Comics supervillains

* Bluestreak (co ...

, leaving Skybolt as the basis of the UK's independent nuclear deterrent in the 1960s. Without Skybolt, the V-bombers of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) were likely to have become obsolete through being unable to penetrate the improved air defences that the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

was expected to deploy by the 1970s.

At Nassau, Macmillan rejected Kennedy's other offers, and pressed him to supply the UK with Polaris missiles. These represented more advanced technology than Skybolt, and the US was not inclined to provide them except as part of a Multilateral Force The Multilateral Force (MLF) was an American proposal to produce a fleet of ballistic missile submarines and warships, each crewed by international NATO personnel, and armed with multiple nuclear-armed Polaris ballistic missiles. Its mission would ...

within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

(NATO). Under the Nassau Agreement the US agreed to provide the UK with Polaris. The agreement stipulated that the UK's Polaris missiles would be assigned to NATO as part of a Multilateral Force, and could be used independently only when "supreme national interests" intervened.

The Nassau Agreement became the basis of the Polaris Sales Agreement

The Polaris Sales Agreement was a treaty between the United States and the United Kingdom which began the UK Polaris programme. The agreement was signed on 6 April 1963. It formally arranged the terms and conditions under which the Polaris mi ...

, a treaty which was signed on 6 April 1963. Under this agreement, British nuclear warheads were fitted to Polaris missiles. As a result, responsibility for Britain's nuclear deterrent passed from the RAF to the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. The President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency i ...

, Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

, cited Britain's dependence on the United States under the Nassau Agreement as one of the main reasons for his veto of Britain's application for admission to the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisb ...

(EEC) on 14 January 1963.

Background

British nuclear deterrent

During the early part of theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Britain had a nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s project, codenamed Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the ...

. At the Quebec Conference in August 1943, the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

and the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

, Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, signed the Quebec Agreement, which merged Tube Alloys with the American Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

to create a combined British, American and Canadian project. The British Government trusted that the United States would continue to share nuclear technology, which it regarded as a joint discovery, after the war, but the United States Atomic Energy Act of 1946

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (McMahon Act) determined how the United States would control and manage the nuclear technology it had jointly developed with its World War II allies, the United Kingdom and Canada. Most significantly, the Act ruled ...

(McMahon Act) ended technical cooperation.

Fearing a resurgence of United States isolationism

United States non-interventionism primarily refers to the foreign policy that was eventually applied by the United States between the late 18th century and the first half of the 20th century whereby it sought to avoid alliances with other nations ...

, and Britain losing its great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

status, the British Government restarted its own development effort, now codenamed High Explosive Research

High Explosive Research (HER) was the British project to develop atomic bombs independently after the Second World War. This decision was taken by a cabinet sub-committee on 8 January 1947, in response to apprehension of an American retur ...

. The first British atomic bomb was tested in Operation Hurricane

Operation Hurricane was the first test of a Nuclear weapons of the United Kingdom, British atomic device. A plutonium Nuclear weapon design#Implosion-type weapon, implosion device was detonated on 3 October 1952 in Main Bay, Trimouille Island ...

on 3 October 1952. The subsequent British development of the hydrogen bomb, and a favourable international relations climate created by the Sputnik Crisis

The Sputnik crisis was a period of public fear and anxiety in Western nations about the perceived technological gap between the United States and Soviet Union caused by the Soviets' launch of ''Sputnik 1'', the world's first artificial satelli ...

, led to the McMahon Act being amended in 1958, resulting in the restoration of the nuclear Special Relationship

The Special Relationship is a term that is often used to describe the politics, political, social, diplomacy, diplomatic, culture, cultural, economics, economic, law, legal, Biophysical environment, environmental, religion, religious, military ...

in the form of the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement, which allowed Britain to acquire nuclear weapons systems from the United States.

Britain's nuclear weapons armament was initially based on

Britain's nuclear weapons armament was initially based on free-fall bomb

An unguided bomb, also known as a free-fall bomb, gravity bomb, dumb bomb, or iron bomb, is a conventional or nuclear aircraft-delivered bomb that does not contain a guidance system and hence simply follows a ballistic trajectory. This describe ...

s delivered by the V-bombers of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF). With the development of the hydrogen bomb, a nuclear strike on the UK could kill most of the population and disrupt or destroy the political and military chains of command. The UK therefore adopted a counterforce strategy, targeting the airbases from which bombers could launch attacks on the UK, and knocking them out before they could do so.

The possibility of the manned bomber becoming obsolete by the late 1960s in the face of improved air defences was foreseen. One solution was the development of long-range missiles. In 1953, the Assistant Chief of the Air Staff (Operational Requirements), Air Vice-Marshal

Air vice-marshal (AVM) is a two-star air officer rank which originated in and continues to be used by the Royal Air Force. The rank is also used by the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence and it is sometimes ...

Geoffrey Tuttle, requested a specification for a ballistic missile

A ballistic missile is a type of missile that uses projectile motion to deliver warheads on a target. These weapons are guided only during relatively brief periods—most of the flight is unpowered. Short-range ballistic missiles stay within the ...

with range, and work commenced at the Royal Aircraft Establishment

The Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) was a British research establishment, known by several different names during its history, that eventually came under the aegis of the Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom), UK Ministry of Defence (MoD), bef ...

in Farnborough later that year. In April 1955, the Commander-in-Chief of RAF Bomber Command

RAF Bomber Command controlled the Royal Air Force's bomber forces from 1936 to 1968. Along with the United States Army Air Forces, it played the central role in the strategic bombing of Germany in World War II. From 1942 onward, the British bo ...

, Air Chief Marshal

Air chief marshal (Air Chf Mshl or ACM) is a high-ranking air officer originating from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. An air chief marshal is equivalent to an Admir ...

Sir George Mills expressed his dissatisfaction with the counterforce strategy, and argued for a countervalue one that targeted administration and population centres for their deterrent effect.

At a North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

(NATO) meeting in Paris in December 1953, United States Secretary of Defense

The United States secretary of defense (SecDef) is the head of the United States Department of Defense, the executive department of the U.S. Armed Forces, and is a high ranking member of the federal cabinet. DoDD 5100.1: Enclosure 2: a The s ...

, Charles E. Wilson, raised the possibility of a joint medium-range ballistic missile

A medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) is a type of ballistic missile with medium range, this last classification depending on the standards of certain organizations. Within the U.S. Department of Defense, a medium-range missile is defined by ...

(MRBM) development programme. Talks were held in June 1954, resulting in the signing of an agreement on 12 August 1954. The United Kingdom with United States support would develop an MRBM, which was called Blue Streak

Blue Streak or Bluestreak may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Blue Streak'' (album), a 1995 album by American blues guitarist Luther Allison

* Blue Streak (comics), a secret identity used by three separate Marvel Comics supervillains

* Bluestreak (co ...

. It was initially estimated to cost £70 million (equivalent to £ in ), with the United States paying 15 per cent. By 1958, the project was in trouble. Its deployment was still years away, but the United States was supplying American-built Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding æsir, god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred trees and groves in Germanic paganism and mythology, sacred groves ...

intermediate-range ballistic missiles under Project Emily

Project Emily was the deployment of American-built Thor intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) in the United Kingdom between 1959 and 1963. Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command operated 60 Thor missiles, dispersed to 20 RAF air stations ...

, and there were concerns about liquid fuelled Blue Streak's vulnerability to a pre-emptive nuclear strike

In nuclear strategy, a first strike or preemptive strike is a preemptive surprise attack employing overwhelming force. First strike capability is a country's ability to defeat another nuclear power by destroying its arsenal to the point where t ...

.

To extend the effectiveness and operational life of the V-bombers, an Operational Requirement

An Operational Requirement, commonly abbreviated OR, was a United Kingdom (UK) Air Ministry document setting out the required characteristics for a future (i.e., as-yet unbuilt) military aircraft or weapon system.

The numbered OR would describe ...

(OR.1132), was issued on 3 September 1954 for an air-launched, rocket-propelled standoff missile

Standoff weapons are missiles or bombs which may be launched from a distance sufficient to allow attacking personnel to evade the effect of the weapon or defensive fire from the target area. Typically, they are used against land- and sea-based targ ...

with a range of that could be launched from a V-bomber. This became Blue Steel. The Ministry of Supply

The Ministry of Supply (MoS) was a department of the UK government formed in 1939 to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to all three British armed forces, headed by the Minister of Supply. A separate ministry, however, was responsible for aircr ...

placed a development contract with Avro

AVRO, short for Algemene Vereniging Radio Omroep ("General Association of Radio Broadcasting"), was a Dutch public broadcasting association operating within the framework of the Nederlandse Publieke Omroep system. It was the first public broad ...

in March 1956, and it entered service in December 1962. By this time it was anticipated that even with Blue Steel, the air defences of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

would soon improve to the extent that V-bombers might find it difficult to attack their targets, and there were calls for the development of the Blue Steel Mark II with a range of at least . Despite the name, this was a whole new missile, and not a development of Mark I. The Minister of Aviation

The Ministry of Aviation was a department of the United Kingdom government established in 1959. Its responsibilities included the regulation of civil aviation and the supply of military aircraft, which it took on from the Ministry of Supply. ...

, Duncan Sandys

Edwin Duncan Sandys, Baron Duncan-Sandys (; 24 January 1908 – 26 November 1987), was a British politician and minister in successive Conservative governments in the 1950s and 1960s. He was a son-in-law of Winston Churchill and played a key r ...

, insisted that priority be accorded to getting the Mark I into service, and the Mark II was cancelled at the end of 1959.

Skybolt

United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

(USAF) also attempted to extend the operational life of its strategic bombers by developing a stand off missile, the AGM-28 Hound Dog

The North American Aviation AGM-28 Hound Dog was a supersonic, turbojet-propelled, nuclear armed, air-launched cruise missile developed in 1959 for the United States Air Force. It was primarily designed to be capable of attacking Soviet gr ...

. The first production model was delivered to the Strategic Air Command

Strategic Air Command (SAC) was both a United States Department of Defense Specified Command and a United States Air Force (USAF) Major Command responsible for command and control of the strategic bomber and intercontinental ballistic missile ...

(SAC) in December 1959. It carried a W28

W, or w, is the twenty-third and fourth-to-last letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. It represents a consonant, but in some languages it r ...

warhead, and had a range of at high level and at low level. Its circular error probable (CEP) of over at full range was considered acceptable for a warhead of this size. A Boeing B-52 Stratofortress

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress is an American long-range, subsonic, jet-powered strategic bomber. The B-52 was designed and built by Boeing, which has continued to provide support and upgrades. It has been operated by the United States Air ...

could carry two, but the underslung Pratt & Whitney J52

The Pratt & Whitney J52 (company designation JT8A) is an axial-flow dual-spool turbojet engine originally designed for the United States Navy, in the 40 kN (9,000 lbf) class. It powered the A-6 Intruder and the AGM-28 Hound Dog cruise miss ...

engine precluded its carriage by bombers with less underwing clearance like the Convair B-58 Hustler

The Convair B-58 Hustler, designed and produced by American aircraft manufacturer Convair, was the first operational bomber capable of Mach 2 flight.

The B-58 was developed during the 1950s for the United States Air Force (USAF) Strategic Air ...

and the North American XB-70 Valkyrie

The North American Aviation XB-70 Valkyrie was the prototype version of the planned B-70 nuclear-armed, deep-penetration supersonic strategic bomber for the United States Air Force Strategic Air Command. Designed in the late 1950s by North Ame ...

. It entered service in large numbers, with 593 in service by 1963. Numbers declined thereafter to 308 in 1976, but it remained in service until 1977, when it was replaced by the AGM-69 SRAM

The Boeing AGM-69 SRAM (Short-Range Attack Missile) was a nuclear air-to-surface missile. It had a range of up to , and was intended to allow US Air Force strategic bombers to penetrate Soviet airspace by neutralizing surface-to-air missile de ...

. Despite its being superior in performance to Blue Steel, the British showed little interest in Hound Dog. It could not be carried by the Handley Page Victor

The Handley Page Victor is a British jet-powered strategic bomber developed and produced by Handley Page during the Cold War. It was the third and final '' V bomber'' to be operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF), the other two being the Avro ...

, and there were doubts as to whether even the Avro Vulcan

The Avro Vulcan (later Hawker Siddeley Vulcan from July 1963) is a jet-powered, tailless, delta-wing, high-altitude, strategic bomber, which was operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF) from 1956 until 1984. Aircraft manufacturer A.V. Roe and ...

had sufficient ground clearance.

Even as Hound Dog was entering service, the USAF was contemplating a successor. An Advanced Air to Surface Missile (AASM) that could carry a warhead with a range of and a CEP of . Such a missile would make manned bombers competitive with Intercontinental Ballistic Missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

s (ICBMs). However, it would also require significant technological advances. The missile became the AGM-48 Skybolt

The Douglas GAM-87 Skybolt (AGM-48 under the 1962 Tri-service system) was an air-launched ballistic missile (ALBM) developed by the United States during the late 1950s. The basic concept was to allow US strategic bombers to launch their weapons ...

. As costs rose and support diminished, the USAF decreased its specifications to carrying a warhead and a CEP of . This was estimated to cost $893.6 million (equivalent to $ in ). A May 1960 report to the chairman of the President's Science Advisory Committee

The President's Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) was created on November 21, 1957, by President of the United States Dwight D. Eisenhower, as a direct response to the Soviet launching of the Sputnik 1 and Sputnik 2 satellites. PSAC was an upgrad ...

(PSAC), George Kistiakowsky

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Preside ...

, the PSAC Missile Advisory Panel stated that it was unconvinced of the Skybolt's merits, as the new LGM-30 Minuteman

The LGM-30 Minuteman is an American land-based intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) in service with the Air Force Global Strike Command. , the LGM-30G Minuteman III version is the only land-based ICBM in service in the United States and r ...

ICBM would be able to perform the same missions at much lower cost. PSAC therefore recommended in December 1960 that Skybolt be cancelled forthwith. United States Secretary of Defense Thomas S. Gates, Jr., elected not to request further funding for it, but avoided cancellation by reprogramming $70 million (equivalent to $ in )from the previous year's allocation.

A crucial reason for Skybolt's survival was the support it garnered from Britain. Blue Streak was cancelled on 24 February 1960, subject to an adequate replacement being procured from the US. An initial solution appeared to be Skybolt, which combined the range of Blue Streak with the mobile basing of the Blue Steel, and was small enough that two could be carried on the Vulcan bomber. Armed with a British

A crucial reason for Skybolt's survival was the support it garnered from Britain. Blue Streak was cancelled on 24 February 1960, subject to an adequate replacement being procured from the US. An initial solution appeared to be Skybolt, which combined the range of Blue Streak with the mobile basing of the Blue Steel, and was small enough that two could be carried on the Vulcan bomber. Armed with a British Red Snow

Red Snow was a British thermonuclear weapon, based on the US W28 (then called Mark 28) design used in the B28 thermonuclear bomb and AGM-28 Hound Dog missile. The US W28 had yields of and while Red Snow yields are still classified, declassifie ...

warhead, this would improve the capability of the UK's V-bomber force, and extend its useful life into the late 1960s and early 1970s. Like the USAF, the RAF was concerned that ballistic missiles could eventually replace manned bombers.

An institutional challenge came from the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, which was developing a submarine-launched ballistic missile

A submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is a ballistic missile capable of being launched from submarines. Modern variants usually deliver multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), each of which carries a nuclear warhead ...

(SLBM), the UGM-27 Polaris

The UGM-27 Polaris missile was a two-stage solid-fueled nuclear-armed submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM). As the United States Navy's first SLBM, it served from 1961 to 1980.

In the mid-1950s the Navy was involved in the Jupiter missile ...

. The US Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the professional head of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the secretary of the Navy. In a separate capacity as a memb ...

, Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Arleigh Burke

Arleigh Albert Burke (October 19, 1901 – January 1, 1996) was an admiral of the United States Navy who distinguished himself during World War II and the Korean War, and who served as Chief of Naval Operations during the Eisenhower and Kenn ...

, kept the First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed ...

, Lord Mountbatten, apprised of its development. By moving the deterrent out to sea, Polaris offered the prospect of a deterrent that was invulnerable to a first strike, and thereby reduced the risk of a first strike on the British Isles, which would no longer be effective. It also had greater value as a deterrent, because retaliation could not be avoided. It would also restore the Royal Navy to its traditional role as the nation's first line of defence, although not everyone in the navy was on board with that idea. The British Nuclear Deterrent Study Group (BNDSG) produced a study that argued that SLBM technology was as yet unproven, that Polaris would be expensive, and that given the time it would take to build the boats, it could not be deployed before the early 1970s. The Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

Defence Committee approved the acquisition of Skybolt in February 1960.

The Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as "Supermac", he ...

, met with President Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

at Camp David

Camp David is the country retreat for the president of the United States of America. It is located in the wooded hills of Catoctin Mountain Park, in Frederick County, Maryland, near the towns of Thurmont and Emmitsburg, about north-northwe ...

near Washington in March 1960, and secured permission to buy Skybolt without strings attached. In return, the Americans were given permission to base the US Navy's Polaris-equipped ballistic missile submarines at the Holy Loch

The Holy Loch ( gd, An Loch Sianta/Seunta) is a sea loch, a part of the Cowal peninsula coast of the Firth of Clyde, in Argyll and Bute, Scotland.

The "Holy Loch" name is believed to date from the 6th century, when Saint Munn landed there afte ...

in Scotland. The financial arrangement was particularly favourable to Britain, as the US was charging only the unit cost

The unit cost is the price incurred by a company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a com ...

of Skybolt, absorbing all the research and development costs. Mountbatten was disappointed, as was Burke, who now had to face the possible survival of Skybolt at the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metony ...

. Exactly what was agreed with regard to Polaris was not clear; the Americans wanted any later offer of Polaris to be as part of a scheme for deployment of NATO MRBMs known as the Multilateral Force The Multilateral Force (MLF) was an American proposal to produce a fleet of ballistic missile submarines and warships, each crewed by international NATO personnel, and armed with multiple nuclear-armed Polaris ballistic missiles. Its mission would ...

. With the Skybolt agreement in hand, the Minister of Defence

A defence minister or minister of defence is a Cabinet (government), cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from coun ...

, Harold Watkinson

Harold Arthur Watkinson, 1st Viscount Watkinson, (25 January 1910, in Walton on Thames – 19 December 1995, in Bosham) was a British businessman and Conservative Party politician. He was Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation between 1 ...

, announced the cancellation of Blue Streak to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

on 13 April 1960.

American concerns

Skybolt proponents in the USAF hoped that the incomingKennedy administration

John F. Kennedy's tenure as the 35th president of the United States, began with his inauguration on January 20, 1961, and ended with his assassination on November 22, 1963. A Democrat from Massachusetts, he took office following the 1960 p ...

, which took office in January 1961, would be supportive of Skybolt, given its election campaigning on the basis of an alleged missile gap

In the United States, during the Cold War, the missile gap was the perceived superiority of the number and power of the USSR's missiles in comparison with those of the U.S. (a lack of military parity). The gap in the ballistic missile arsenals di ...

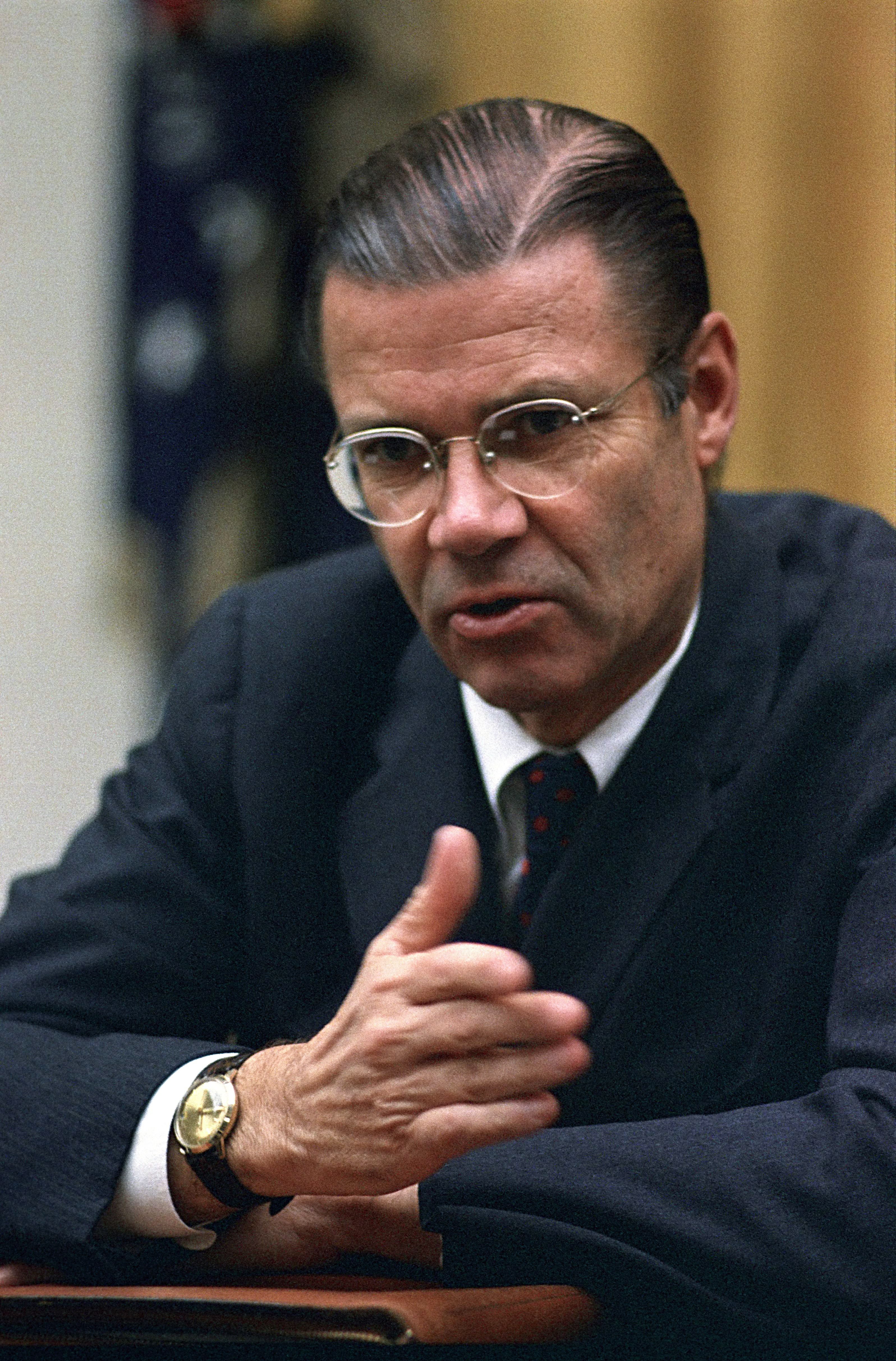

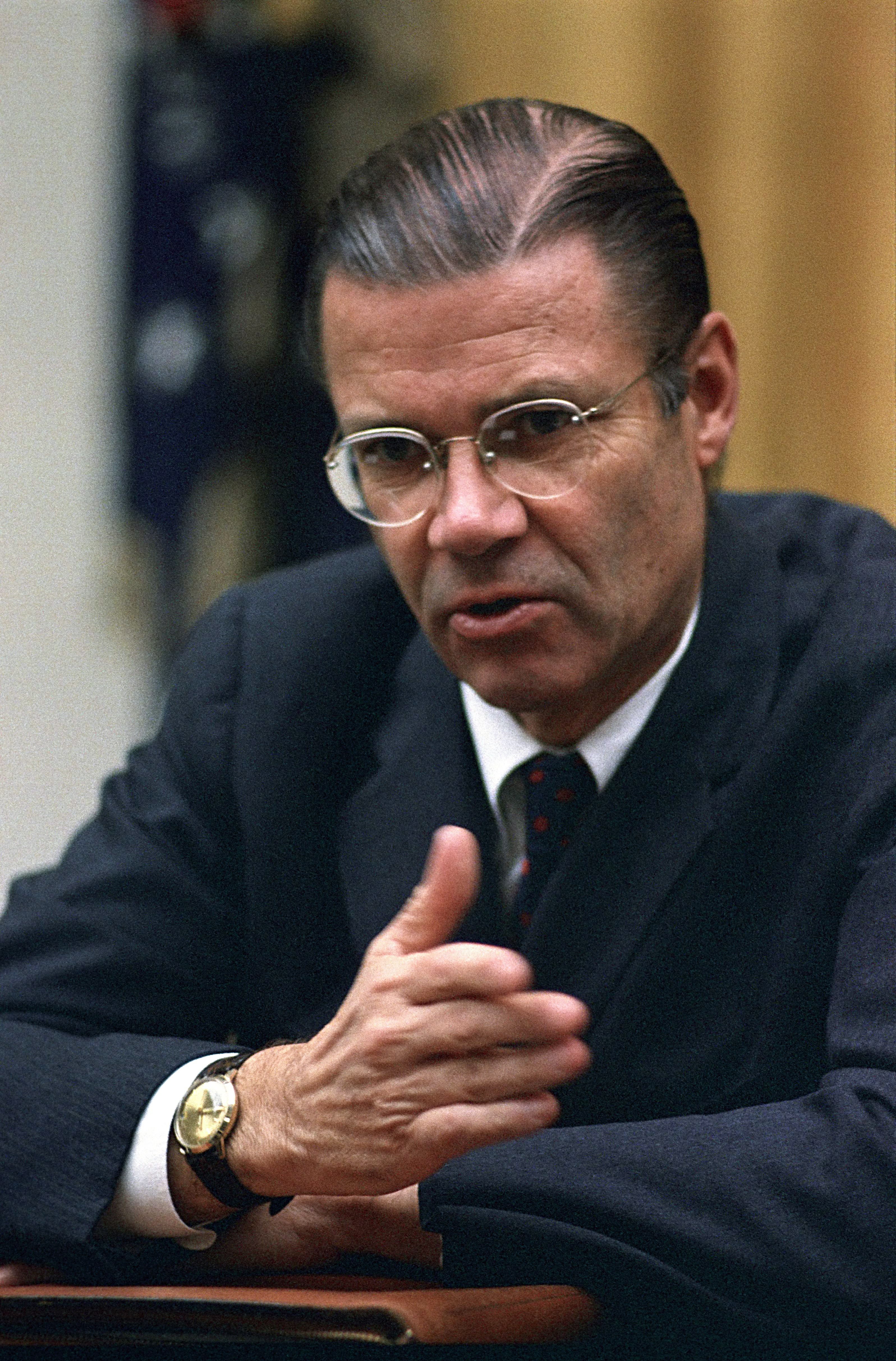

between Soviet and US capabilities. Initially it was; Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the Lis ...

the new Secretary of Defense, defended Skybolt before the Senate Armed Services Committee

The Committee on Armed Services (sometimes abbreviated SASC for ''Senate Armed Services Committee'') is a committee of the United States Senate empowered with legislative oversight of the nation's military, including the Department of Def ...

. He requested $347 million to purchase 92 Skybolt missiles in 1963, with the intention of deploying 1,150 missiles by 1967. However, on 21 October 1961 the USAF raised its estimate of research and development costs to $492.6 million (equivalent to $ in ), an increase of over $100 million (equivalent to $ in ), and production costs were now reckoned at $1.27 billion (equivalent to $ in ), an increase of $591 million (equivalent to $ in ).

The Kennedy Administration adopted a policy of opposition to independent British nuclear forces in April 1961. In a speech at

The Kennedy Administration adopted a policy of opposition to independent British nuclear forces in April 1961. In a speech at Ann Arbor, Michigan

Ann Arbor is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan and the county seat of Washtenaw County, Michigan, Washtenaw County. The 2020 United States census, 2020 census recorded its population to be 123,851. It is the principal city of the Ann Arbor ...

, on 16 June 1962, McNamara stated "limited nuclear capabilities, operating independently, are dangerous, expensive, prone to obsolescence and lacking in credibility as a deterrent," and that "relatively weak national nuclear forces with enemy cities as their targets are not likely to perform even the function of deterrence." The former United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

, Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson (pronounced ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American statesman and lawyer. As the 51st U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to 1953. He was also Truman ...

, was even more blunt; in a speech at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

he stated: "Britain's attempt to play a separate power role – that is, a role apart from Europe, a role based on a 'special relationship' with the United States, a role based on being the head of a Commonwealth which has no political structure or unity or strength and enjoys a fragile and precarious economic relationship – this role is about played out."

The Kennedy administration was concerned that a situation like the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

might repeat itself, one that would once again incite a nuclear threat against the UK from the Soviet Union. The Americans developed a plan to force the UK into the Multilateral Force concept, a dual key arrangement that would allow launch only if both parties agreed. If nuclear weapons were part of a multinational force, attacking them would require attacks on the other hosting countries as well. The US feared that otherwise other countries would want to follow the UK lead and develop their own deterrent forces, leading to a nuclear proliferation problem even among their own allies. If a deterrent was provided by an international force, the need for individual forces would be reduced.

Between 1955 and 1960, the British economy had lagged behind that of the rest of Europe, growing at an average of 2.5 per cent per annum, compared with France's growth of 4.8 per cent, Germany's of 6.4 per cent, and the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisb ...

(EEC) average of 5.3 per cent, and Macmillan devoted much of 1960 to laying the ground for Britain's entry into the EEC. The US was concerned that providing Polaris to Britain would jeopardise Britain's prospects of joining the EEC. Long-term US policy was to persuade the UK to build up its conventional military forces, and to secure admission to the EEC.

McNamara introduced cost-effectiveness analysis

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) is a form of economic analysis that compares the relative costs and outcomes (effects) of different courses of action. Cost-effectiveness analysis is distinct from cost–benefit analysis, which assigns a monetar ...

to defence procurement. Skybolt suffered from rising costs, and the first five test launches were failures. This was not unusual; Polaris and Minuteman had similar problems. What doomed Skybolt was an inability to demonstrate capability beyond that achievable by Hound Dog, Minuteman or Polaris. This meant that there were few advantages for the United States in continuing Skybolt, but at the same time its cancellation would be a powerful political tool for bringing the UK into their Multilateral Force. The British, on the other hand, had cancelled all other projects to concentrate fully on Skybolt. When warned not to put all their eggs in the one basket, the British replied that there was "no other egg, and no other basket". On 7 November 1962, McNamara met with Kennedy, and recommended that Skybolt be cancelled. He then briefed the British Ambassador to the United States

The British Ambassador to the United States is in charge of the British Embassy, Washington, D.C., the United Kingdom's diplomatic mission to the United States. The official title is His Majesty's Ambassador to the United States of America.

T ...

, David Ormsby-Gore. Kennedy agreed to cancel Skybolt on 23 November 1962.

Negotiations

McNamara met withSolly Zuckerman

Solomon "Solly" Zuckerman, Baron Zuckerman (30 May 1904 – 1 April 1993) was a British public servant, zoologist and operational research pioneer. He is best remembered as a scientific advisor to the Allies on bombing strategy in the Second Wo ...

, the UK Chief Scientific Adviser to the Ministry of Defence The Chief Scientific Adviser to the UK's Ministry of Defence is responsible for providing strategic management of science and technology issues in the MOD, most directly through the MOD research budget of well over £1 billion, and sits as a full me ...

on 9 December,

and flew to London to meet with the Minister of Defence, Peter Thorneycroft

George Edward Peter Thorneycroft, Baron Thorneycroft, (26 July 1909 – 4 June 1994) was a British Conservative Party politician. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1957 and 1958.

Early life

Born in Dunston, Staffordshire, Thorn ...

, on 11 December. On arrival he told the media that Skybolt was an expensive and complex program that had suffered five test failures. Kennedy told a television interviewer that "we don't think that we are going to get $2.5 billion worth of national security". US National Security Advisor A national security advisor serves as the chief advisor to a national government on matters of security. The advisor is not usually a member of the government's cabinet but is usually a member of various military or security councils.

National sec ...

McGeorge Bundy

McGeorge "Mac" Bundy (March 30, 1919 – September 16, 1996) was an American academic who served as the U.S. National Security Advisor to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson from 1961 through 1966. He was president of the Ford Founda ...

gave an interview on television in which he stated that the US had no obligation to supply Skybolt to the UK. Thorneycroft had expected McNamara to offer Polaris instead, but found him unwilling to countenance such an offer except as part of a Multinational Force. McNamara was willing to supply Hound Dog, or to allow the British to continue development of Skybolt.

These discussions were reported to the House of Commons by Thorneycroft, leading to a storm of protest. Air Commodore Sir

These discussions were reported to the House of Commons by Thorneycroft, leading to a storm of protest. Air Commodore Sir Arthur Vere Harvey

Arthur Vere Harvey, Baron Harvey of Prestbury, Knight Bachelor, Kt. (31 January 1906 – 5 April 1994) was a senior Royal Air Force officer and a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as a Member of Parliament (Un ...

pointed out that while Skybolt had suffered five test failures, Polaris had thirteen failures in its development. He went on to state "that some of us on this side, who want to see Britain retain a nuclear deterrent, are highly suspicious of some of the American motives... and say that the British people are tired of being pushed around". Liberal Party leader Jo Grimond

Joseph Grimond, Baron Grimond, (; 29 July 1913 – 24 October 1993), known as Jo Grimond, was a British politician, leader of the Liberal Party for eleven years from 1956 to 1967 and again briefly on an interim basis in 1976.

Grimond was a lo ...

asked: "Does not this mark the absolute failure of the policy of the independent deterrent? Is it not the case that everybody else in the world knew this, except the Conservative Party in this country? Is it not the case that the Americans gave up production of the B-52, which was to carry Skybolt, nine months ago?"

As the Skybolt Crisis came to the boil in the UK, an emergency meeting between Macmillan and Kennedy was arranged to take place in Nassau, Bahamas

Nassau ( ) is the capital and largest city of the Bahamas. With a population of 274,400 as of 2016, or just over 70% of the entire population of the Bahamas, Nassau is commonly defined as a primate city, dwarfing all other towns in the country. ...

. Accompanying Macmillan were British Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

, Lord Home

Earl of Home ( ) is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1605 for Alexander Home of that Ilk, 6th Lord Home. The Earl of Home holds, among others, the subsidiary titles of Lord Home (created 1473), and Lord Dunglass (1605), i ...

; Thorneycroft; Sandys; and Zuckerman. Naval expertise was supplied by Vice-Admiral Michael Le Fanu

Admiral of the Fleet (Royal Navy), Admiral of the Fleet Sir Michael Le Fanu (2 August 1913 – 28 November 1970) was a Royal Navy officer. He fought in the Second World War as gunnery officer in a cruiser operating in the Home Fleet during the N ...

. Ormsby-Gore flew to Nassau with Kennedy. En route, he brokered a deal whereby Britain and the United States would continue development of Skybolt, with each paying half the cost, the American half being a kind of termination fee. In London, over one hundred Conservative members of Parliament, nearly one third of the parliamentary party, signed a motion urging Macmillan to ensure that Britain remained an independent nuclear power.

Talks opened with Macmillan detailing the history of the Anglo-American Special Relationship, going back to the Second World War. He rejected the deal that Kennedy and Ormsby-Gore had reached. It would cost Britain about $100 million (equivalent to $ in ), and was not politically viable in the wake of recent public comments about Skybolt. Kennedy then offered Hound Dog. Macmillan turned this down on technical grounds, although it had not been subjected to a detailed assessment, and probably would have worked for the RAF into the 1970s, as it did for the USAF.

It therefore came down to Polaris, which the US did not wish to supply except as part of a Multinational Force. Macmillan was emphatic that he would commit the submarines to NATO only if they could be withdrawn in case of a national emergency. When pressed by Kennedy as to what sort of emergencies he had in mind, Macmillan mentioned the Soviet threats at the time of the Suez Crisis, Iraqi aggression against Kuwait, or a threat to Singapore. The British nuclear deterrent was not just for deterring attacks on the UK, but to underwrite Britain's role as a great power. In the end, Kennedy did not wish to see Macmillan's government collapse, which would imperil Britain's entry into the EEC, so a face-saving compromise was found, which was released as a joint statement on 21 December 1962:

Canadian interlude

It was customary for the Canadians to be consulted when there was a meeting between the British and American leaders on the North American side of the Atlantic. This nicety was not observed when the Nassau conference was arranged, but thePrime Minister of Canada

The prime minister of Canada (french: premier ministre du Canada, link=no) is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the Confidence and supply, confidence of a majority the elected Hou ...

, John Diefenbaker

John George Diefenbaker ( ; September 18, 1895 – August 16, 1979) was the 13th prime minister of Canada, serving from 1957 to 1963. He was the only Progressive Conservative party leader between 1930 and 1979 to lead the party to an electio ...

invited Macmillan to a meeting in Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

. Macmillan countered with an offer to meet in Nassau after the Skybolt issue was resolved. Kennedy and Diefenbaker loathed each other, and Kennedy made plans to leave early to avoid Diefenbaker, but Macmillan persuaded Kennedy to stay for a lunch meeting. Kennedy later described the uncomfortable meeting as being like "three whores at a christening".

Nuclear weapons had become a political issue in Canada in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

, when Canadian Bomarc surface-to-air missile

A surface-to-air missile (SAM), also known as a ground-to-air missile (GTAM) or surface-to-air guided weapon (SAGW), is a missile designed to be launched from the ground to destroy aircraft or other missiles. It is one type of anti-aircraft syst ...

s had sat idly by while the country was threatened with a nuclear attack due to Diefenbaker's insistence that their nuclear warheads be stored outside Canada, an arrangement which the Americans regarded as impractical. Macmillan briefed Diefenbaker on the Nassau Agreement, which Diefenbaker took to mean that manned bombers were now considered obsolete. This gave him further cause to continue to delay a decision on the Bomarc warheads, which were intended to shoot down bombers. He did, however, express interest in Canadian participation in the Multilateral Force.

Outcome

On 22 December, after the Nassau conference had ended, the USAF conducted the sixth and final test flight of Skybolt, having received explicit permission to do so fromRoswell Gilpatric

Roswell Leavitt Gilpatric (November 4, 1906 – March 15, 1996) was a New York City corporate attorney and government official who served as Deputy Secretary of Defense from 1961–64, when he played a pivotal role in the high-stake strategie ...

, the United States Deputy Secretary of Defense

The deputy secretary of defense (acronym: DepSecDef) is a statutory office () and the second-highest-ranking official in the Department of Defense of the United States of America.

The deputy secretary is the principal civilian deputy to the se ...

, in McNamara's absence. The test was a success. Kennedy was furious, but Macmillan remained confident that the Americans had "determined to kill Skybolt on good general grounds—not merely to annoy us or drive Great Britain out of the nuclear business". The successful test raised the possibility that the USAF might get the Skybolt project reinstated, and the Americans would renege on the Nassau Agreement. This did not occur; Skybolt was officially cancelled on 31 December 1962.

Macmillan placed the Nassau Agreement before the cabinet on 3 January 1963. He made the case for Britain retaining nuclear weapons. He asserted that it would not be in the best interest of the Western Alliance for all knowledge of the technology to reside with the United States; that possession of an independent nuclear capability gave Britain the ability to respond to threats from the Soviet Union even when the United States was not inclined to support Britain; and that possession of nuclear weapons gave Britain a voice in nuclear disarmament talks. However, concerns were expressed that the dependence on the United States would necessarily diminish Britain's influence on world affairs. Thorneycroft addressed the view that Britain should provide a nuclear deterrent from its own resources. He pointed out that Polaris represented $800 million (equivalent to $ in ) in research and development costs that the United Kingdom would save. Nonetheless, the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

, Selwyn Lloyd

John Selwyn Brooke Lloyd, Baron Selwyn-Lloyd, (28 July 1904 – 18 May 1978) was a British politician. Born and raised in Cheshire, he was an active Liberal as a young man in the 1920s. In the following decade, he practised as a barrister and ...

, was still concerned at the cost.

Polaris Sales Agreement

The Polaris Sales Agreement was a treaty between the United States and the United Kingdom which began the UK Polaris programme. The agreement was signed on 6 April 1963. It formally arranged the terms and conditions under which the Polaris mi ...

, a treaty under the terms of which the US supplied Polaris missiles, which was signed on 6 April 1963. The missiles were equipped with British ET.317 warheads. The UK retained its deterrent force, although its control passed from the RAF to the Royal Navy. Polaris was a better weapon system for the UK's needs, and has been referred to as "almost the bargain of the century", and an "amazing offer". The V-bombers were immediately reassigned to NATO under the terms of the Nassau Agreement, carrying tactical nuclear weapon

A tactical nuclear weapon (TNW) or non-strategic nuclear weapon (NSNW) is a nuclear weapon that is designed to be used on a battlefield in military situations, mostly with friendly forces in proximity and perhaps even on contested friendly territo ...

s, as were the Polaris submarines when they entered service in 1968. The Polaris Sales Agreement was amended in 1980 to provide for the purchase of Trident

A trident is a three- pronged spear. It is used for spear fishing and historically as a polearm.

The trident is the weapon of Poseidon, or Neptune, the God of the Sea in classical mythology. The trident may occasionally be held by other marine ...

. British politicians did not like to talk about "dependence" on the United States, preferring to describe the Special Relationship as one of "interdependence".

As had been feared, the President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency i ...

, Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

, vetoed Britain's application for admission to the EEC on 14 January 1963, citing the Nassau Agreement as one of the main reasons. He argued that Britain's dependence on United States through the purchase of Polaris rendered it unfit to be a member of the EEC. The US policy of attempting to force Britain into their Multilateral Force proved to be a failure in light of this decision, and there was a lack of enthusiasm for it from the other NATO allies too. By 1965, the Multilateral Force was fading away. The NATO Nuclear Planning Group

The Nuclear Planning Group was established in December 1966 to allow better communication, nuclear consultation and involvement among Allied NATO nations to deal with matters related to nuclear policy issues. During the period of the Cold War, NATO ...

gave NATO members a voice in the planning process without full access to nuclear weapons. The Standing Naval Force Atlantic

Standing NATO Maritime Group One (SNMG1) is one of NATO's standing naval maritime immediate reaction forces. SNMG1 consists of four to six destroyers and frigates. Its role is to provide NATO with an immediate operational response capability.

Hi ...

was established as a joint naval task force, to which various nations contributed ships rather than ships having mixed crews.

In Canada, the Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

, Lester B. Pearson

Lester Bowles "Mike" Pearson (23 April 1897 – 27 December 1972) was a Canadian scholar, statesman, diplomat, and politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Canada from 1963 to 1968.

Born in Newtonbrook, Ontario (now part of ...

, came out strongly in favour of Canada accepting nuclear weapons. He encountered dissent from within his own Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

, notably from Pierre Trudeau, but opinion polls indicated that he was staking out a position held by the overwhelming majority of Canadians. Nor was Diefenbaker's own Progressive Conservative Party united over the issue. On 3 February 1963, Douglas Harkness

Douglas Scott Harkness, (March 29, 1903 – May 2, 1999) was a Canadian politician.

Early life and military service

He was born in Toronto, Ontario, and moved to Calgary, Alberta in 1929. He graduated from the University of Alberta, then farm ...

, the Minister of National Defence, submitted his resignation. Two days later, Diefenbaker's government was toppled by a motion of no confidence

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or mana ...

in the House of Commons of Canada

The House of Commons of Canada (french: Chambre des communes du Canada) is the lower house of the Parliament of Canada. Together with the Crown and the Senate of Canada, they comprise the bicameral legislature of Canada.

The House of Common ...

. An election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

followed, and Pearson became the Prime Minister on 8 April 1963.

Macmillan's government lost a series of by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

s in 1962, and was shaken by the Profumo affair

The Profumo affair was a major scandal in twentieth-century Politics of the United Kingdom, British politics. John Profumo, the Secretary of State for War in Harold Macmillan's Conservative Party (UK), Conservative government, had an extramar ...

in 1963. In October 1963, on the eve of the annual Conservative Party Conference

The Conservative Party Conference (CPC) is a four-day national conference event held by the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom. It takes place every year around October during the British party conference season, when the House of Commons is ...

, Macmillan fell ill with what was initially feared to be inoperable prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is cancer of the prostate. Prostate cancer is the second most common cancerous tumor worldwide and is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality among men. The prostate is a gland in the male reproductive system that sur ...

. His doctors assured him that it was benign, and that he would make a full recovery, but he took the opportunity to resign on the grounds of ill-health. He was succeeded by Lord Home, who renounced his peerage and as Alec Douglas-Home campaigned on Britain's nuclear deterrent in the 1964 election. While the issue was of low importance in the minds of the electorate, it was an issue on which Douglas-Home felt passionately, and on which the majority of voters supported his position. The Labour Party election manifesto called for the Nassau Agreement to be renegotiated, and on 5 October 1964, the leader of the Labour Party, Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

, criticised the independent British deterrent as neither independent, nor British, nor a deterrent. Douglas-Home narrowly lost the election to Wilson. In office, Labour retained Polaris, and assigned the Polaris boats to NATO, in accord with the Nassau Agreement.

Kennedy, stung by the entire issue, commissioned a detailed report on the events and what lessons could be learned from them by Richard Neustadt

Richard Elliott Neustadt (June 26, 1919 – October 31, 2003) was an American political scientist specializing in the United States presidency. He also served as adviser to several presidents. He was the author of the books ''Presidential Power' ...

, one of his advisors. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Jacqueline Lee Kennedy Onassis ( ; July 28, 1929 – May 19, 1994) was an American socialite, writer, photographer, and book editor who served as first lady of the United States from 1961 to 1963, as the wife of President John F. Kennedy. A pop ...

recalled him reading the report and commenting that "If you want to know what my life is like, read this." The report was declassified in 1992, and published as ''Report to JFK: The Skybolt Crisis in Perspective''.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* {{Portal bar, Politics, United Kingdom, Nuclear technology 1962 in British politics 1962 in American politics 1962 in international relations United Kingdom–United States relations Nuclear history of the United Kingdom Nassau, Bahamas Polaris (UK nuclear programme) Presidency of John F. Kennedy Harold Macmillan